Medieval Siege Warfare I.

Although it might not seem so at first glance, siege warfare played a much more significant role in medieval military tactics than field battles. The outcomes of battles were always uncertain and rarely had long-term effects, whereas the capture and occupation (or destruction) of an enemy's fortified stronghold could be strategically leveraged in the longer term. It is no surprise, then, that medieval warfare conflicts were about 70% (or more) focused on sieges, with the remaining 30% or less involving battles or smaller skirmishes.

The basic methods for capturing settlements, fortresses, castles, or cities remained the same from the early to the late Middle Ages. The first step was to cut off all access routes (and ideally to completely encircle the location). Then, the attackers would fill in the moat (if the structure had one) at specific points and finally create a breach in the wall, wooden palisade, or force open the gate. Ideally, these efforts were combined with attempts to storm the walls or ramparts using ladders. Another technique used was undermining a section of the walls through the moat to increase the chances of the wall collapsing at that section.

For the purpose of protecting soldiers filling in the moat or carrying battering rams, simple covered shelters were built, which were mobile thanks to crude wheels and covered with raw hides to protect them from being set on fire. Siege towers on wheels were also constructed to facilitate storming the walls. These towers were similarly protected and always taller than the walls so that attackers could lower a drawbridge directly onto the wall's crest, allowing them to cross over while till that moment being shielded from enemy fire behind the lifted drawbridge.

Until the advent of black powder, various types of siege engines were used to damage walls, gates, and inner buildings, or to create breaches. These devices are collectively referred to as "mechanical artillery." Essentially, there were two main types. The first were machines with a bow and string, designed for direct fire, which were derived from ancient designs (ballista). These machines typically shot arrows about 1 meter long, which were useful for destroying living forces and starting fires. The second type consisted of machines that operated on the principle of a two-armed lever, which used counterweights to launch various projectiles in an arched trajectory. The origin of this type of machine is more obscure, and it is uncertain if they can be considered a legacy of antiquity. There is some evidence of their use in Western Europe in the 9th century, allegedly operated by specialists from Byzantium. It was these machines, operating on this principle, that became an essential and iconic part of medieval siege warfare. The period of general adoption of mechanical artillery across Europe can be considered the transition from the early to the high Middle Ages, roughly from the 10th to the 12th century.

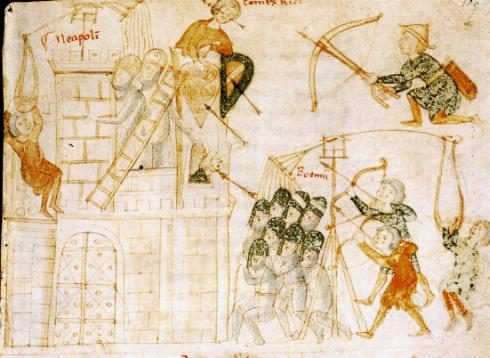

Emperor Henry VI besieges Naples. Bohemian soldiers (Boemi) operate a light sling – pierrier. The defenders have the same machine on the walls. Illustration from the chronicle of Peter de Ebulo "Liber ad honorem Augusti" (1196). Wikimedia Commons

Classifying these machines operating on the principle of a two-armed lever is not easy, as depictions in contemporary illustrations can be misleading, and the language of written sources is not always helpful. For example, Bohemian (old Czech) sources typically use the general term "prak", (Sling) which does not indicate the size or power of the machine. Fortunately, sources written in other languages are a bit more specific, allowing for a rough classification, using for exemple French terminology. These machines can be found in various depictions from the 12th century to the end of the Middle Ages:

Pierrière: The smallest siege sling, which used human power as a counterweight, with men pulling ropes or chains. It had a range of about 50 meters, threw projectiles weighing around 12 kg, and was operated by 8-16 men. A stronger version of this machine, called the Bricole, had additional lead weights, allowing it to shoot up to 80 meters with projectiles weighing up to 30 kg.

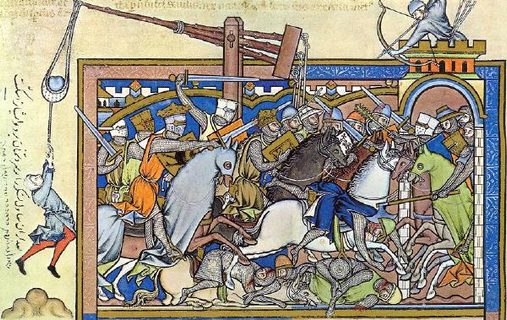

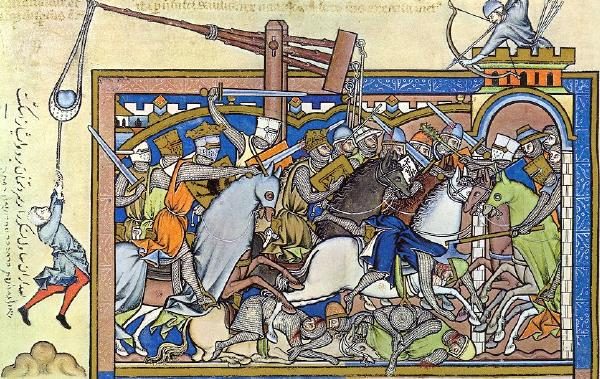

Use of a light siege sling (pierrier or bricole) during a siege. Illustration from the so-called Morgan Bible (or Maciejowski Bible), mid-13th century. Wikimedia Commons

Mangonneau: A larger siege sling with a fixed counterweight, which was wound using a treadwheel. It shot projectiles weighing up to 100 kg at a distance of about 150 meters and was operated by 12 men.

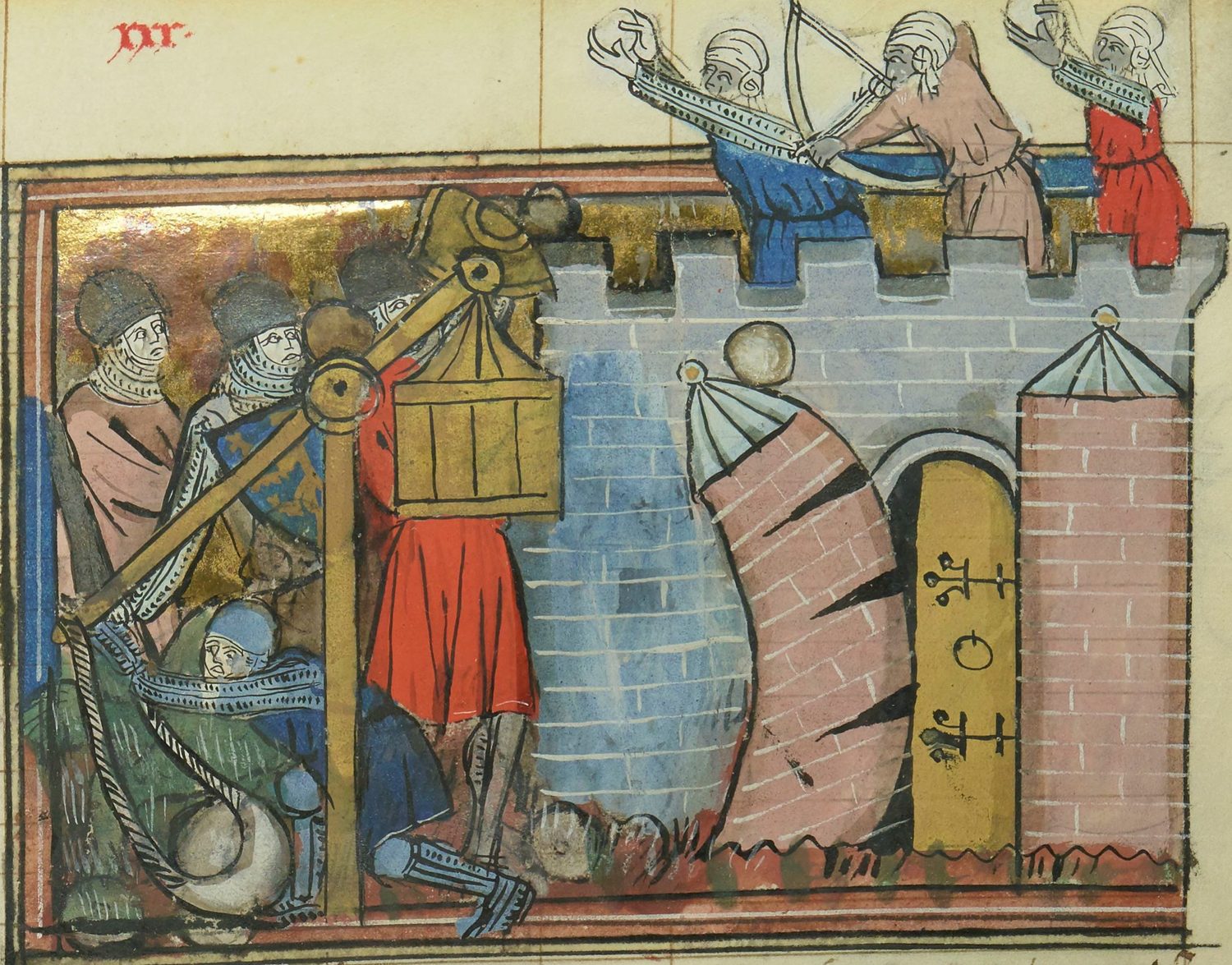

Use of a large trebuchet (trébuchet) by Crusaders during the siege of Nicaea (1097). Illustration from the romance of Godefroy de Bouillon, 1337. Wikimedia Commons

Trébuchet (Trebuchet): The largest siege trebuchet with a range of 200 meters or more. It usually had a movable counterweight, could shoot projectiles weighing 125 kg, and was operated by 60 or more people, including support craftsmen.

Building these machines was not easy and required good knowledge of the different properties of various types of wood, which was essential for selecting the appropriate material for each part of the machine. The main supporting beams were usually made of strong oak, while fir was used for parts under tension and friction. Elm was used for parts under pure tension.

Regarding the selection of projectiles, in addition to carved stones, the use of animal carcasses or barrels of feces to spread disease within the besieged area and incendiary projectiles (e.g., barrels filled with flammable material) to start fires in the target area should be mentioned.

Mechanical artillery machines were used until the end of the Middle Ages, although from the second half of the 14th century, they began to be challenged by black powder firearms, which eventually supplanted mechanical artillery at the beginning of the 16th century.

Related products

And what to read next?

The Tale of Sir Radzig’s Sword

In the heart of Bohemian workshops, a replica has been forged of the sword known to millions of players around the world. In Kingdom Come: Deliverance, Sir Radzig Kobyla’s sword carries the weight of destiny. It was meant to be a gift from a father, but fell into the hands of the enemy. In the end, however, it was reclaimed and returned to its rightful owner. It became a symbol of loyalty and of the strength to endure in the face of adversity.

The Hussite Shock to Europe: How a Small Nation Changed the Continent

The Hussites were not merely heretics, as their enemies called them. They were the first to prove that it was possible to defend one's faith even against the whole of Christian Europe.

Trosky Castle

Trosky, the magical symbol of the Bohemian Paradise, hides a labyrinth of underground tunnels.

Jan Žižka of Trocnov, an ode to a brilliant military leader

He ranks among the most significant medieval commanders in European and Czech history—Jan Žižka of Trocnov (c. 1360 – October 11, 1424) is considered one of the undefeated giants of world battlefields. He gained fame for his use of the wagon fort, a highly effective defensive technique. His Hussite soldiers were pioneers in the use of firearms, particularly the "píšťala," a term from which the English word "pistol" is derived.