Medieval Siege Warfare II.

The art of siege warfare in the Middle Ages drew from the heritage of antiquity. Although some methods and machines had to be rediscovered and sometimes improved upon, the offensive strategies still relied on devices categorized as so-called "mechanical artillery". A major innovative element was the invention of gunpowder.

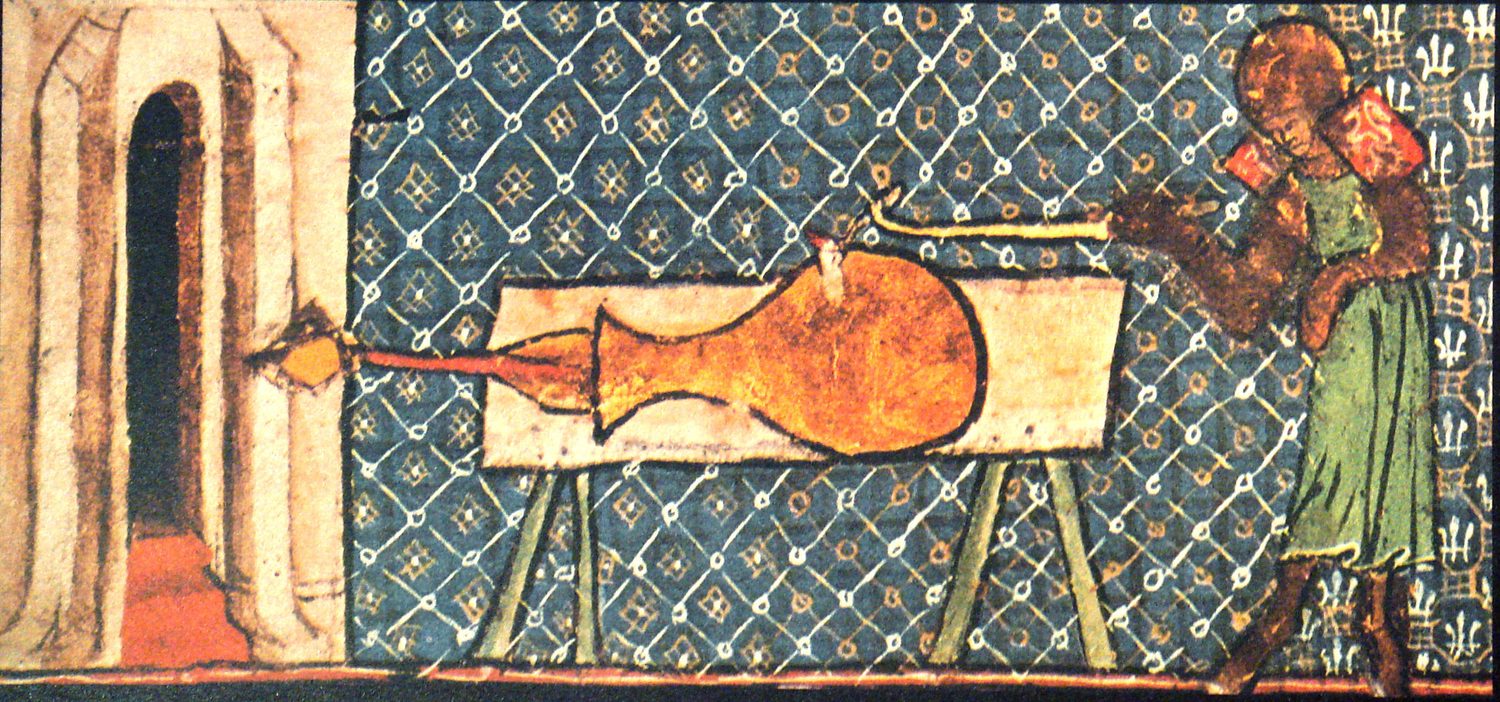

While gunpowder had been known in the Far East since the 11th century in China, its knowledge in Europe is reliably documented only from the second half of the 13th century. The first documented recipe for gunpowder was provided by the English theologian and scholar with alchemical knowledge, Franciscan friar Roger Bacon, in 1267. However, the first proven depiction of a gunpowder firearm is known from the work of Walter de Milemete, dated to 1326. From this point on, throughout the 14th century, gunpowder firearms continued to develop – aided by cities that provided a suitable foundation for the emergence and growth of the gunsmith craft, and where new crafts like those of saltpetre men and powder makers also emerged. They learned to obtain the key ingredient for gunpowder, saltpetre (originally imported to Europe from the East), and produce gunpowder itself.

First known depiction of a cannon in the Middle Ages. Illustration from Walter de Milemete's "De Nobilitatibus, Sapientii et Prudentiis Regum," 1326. Wikimedia Commons

Various calibers of cannons began developing throughout the 14th century, successfully complementing mechanical artillery in attacking and defending fortified places, while handheld firearms – hackbuts, hand cannons and the first primitive handguns – were initially less impactful. However, the significance of all firearms increased from the early 15th century onwards. Firearms, including cannons and handguns, were already present in wars between Polish kings and the Teutonic Knights, in local wars in the German territories of the Holy Roman Empire, in the final phase of the Hundred Years' War in France, and notably in the Hussite Wars in the Kingdom of Bohemia (today's Czech Republic). Firearms increasingly appeared in field battles, but they were most valued during sieges.

Shooting from a simple hand cannon. Bellifortis, Konrad Kyeser, circa 1402. Wikimedia Commons

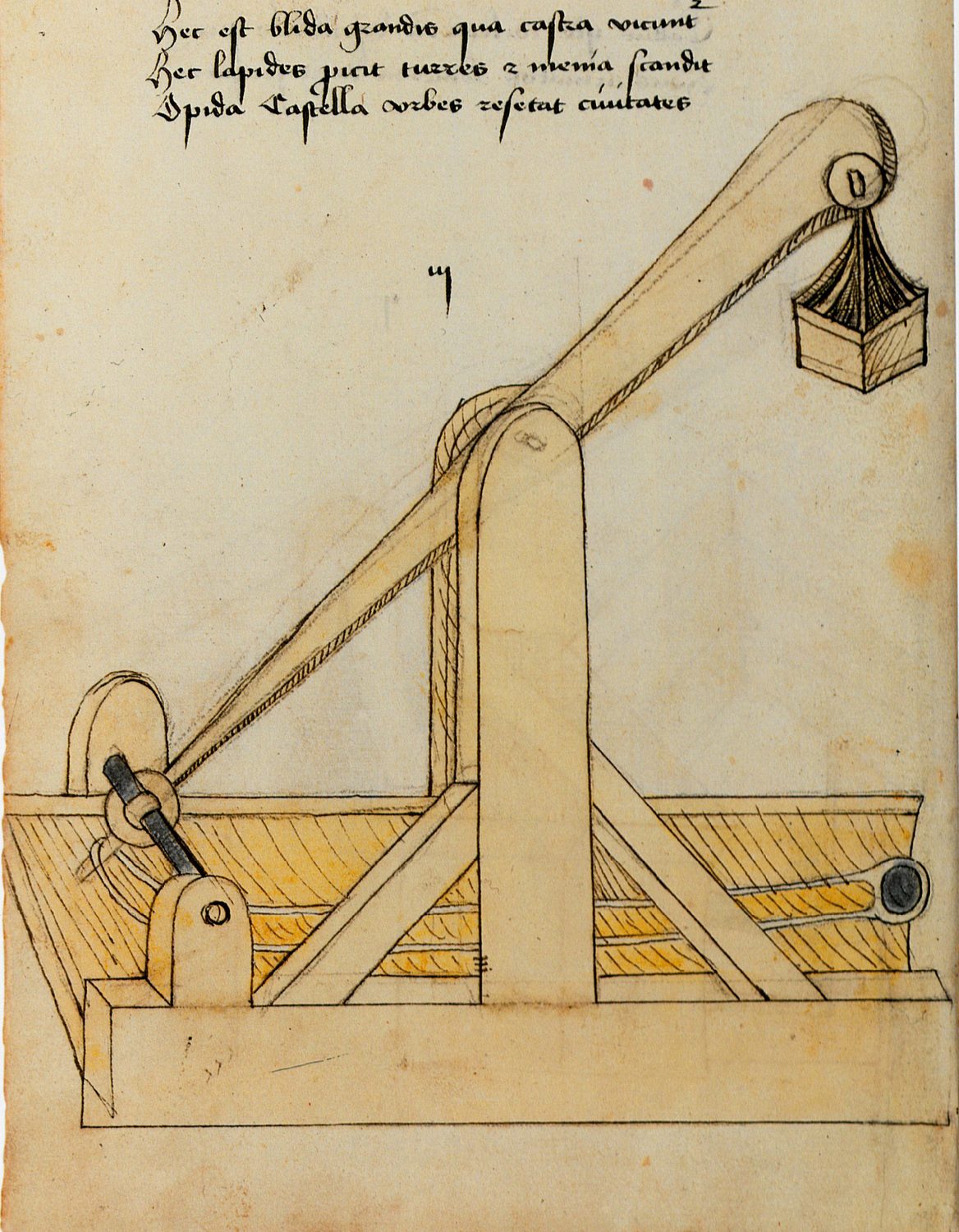

What did this mean for the existing siege warfare tactics? Their foundation remained essentially the same – besiegers built mantlets to protect archers, crossbowmen, and handgunners, constructed movable shelters used during attempts to fill in moats or break down gates with battering rams. However, they now began to build what later terminology would call a sap or approach trench. Using this, they tried to build gun positions as close as possible to the enemy fortifications to maximize the effectiveness of their fire. There was increasing experimentation with ammunition, so alongside stone and lead balls, attempts at firing iron balls or composite shots began to appear, where a hard core of stone or iron was cast into a lead ball, resulting in an effect similar to modern armor-piercing rounds. Firearms gradually found their way into military theoretical works, such as the well-known book by Konrad Kyeser: Bellifortis. Alongside this, there was experimentation with incendiary ammunition and ammunition designed to spread over a large area to hurt or kill as much enemy combatants as possible. Mechanical artillery did not disappear from the battlefield and was used alongside cannons, although the importance of large trebuchets declined throughout the 15th century. Fine examples of such cooperation between old and new artillery can be found in the Hussite Wars. When the Prague citizens besieged Nový Hrad castle near Kunratice in the winter of 1420-1421, they deployed three large siege engines (possibly trebuchets) and an unspecified number of cannons. They also used the aforementioned sap trenches during the siege. The intense bombardment resulted in the total destruction of roofs and parapets, forcing the defenders to surrender. Another example is the siege of Karlštejn Castle, against which the Hussites deployed four large trebuchets, five large cannons, and about 38 small and medium-sized cannons in a near-crossfire. Unlike Nový Hrad, however, Karlštejn withstood the assault.

Large siege engine - trebuchet (also called blida). Bellifortis, Konrad Kyeser, circa 1402. Wikimedia Commons

Precise categorization of early medieval firearms by today's standards is, of course, not applicable to the first firearms of the Middle Ages. Nevertheless, they can be broadly classified by function into several groups. The first group comprises heavy siege cannons, known as bombards, with calibers ranging from 300 to 900 mm. These were used to destroy fortifications, including walls. The second group consists of medium-caliber cannons (howitzers), which ranged from 160 mm to 300 mm. The third group includes light cannons with calibers of 40 to 150 mm (veuglaires, coulverines). Light and medium cannons could be used both in sieges and field battles alike, primarily targeting enemy combatants. When used in sieges, they were employed to destroy wooden elements of fortifications, parapets, and roofs. The last group consists of handheld firearms used by infantry – hand cannons and hackbuts mounted on primitive wooden stocks or mounts, and handguns, which by the 15th century had acquired crude wooden stocks resembling those of later rifles of modern era.

Most cannons had fixed mounts for a long time and had to be transported disassembled on wagons. Only during the 15th century did medium-caliber cannons begin to be equipped with wheels, allowing them to be maneuvered directly on the battlefield and sometimes even transported by being towed by horses, although these cannons were still often transported disassembled on wagons.

The ammunition for the largest and some medium cannons consisted of stone balls, while medium cannons with smaller calibers and handheld firearms used lead balls or lead cylinders. Initially, most firearm barrels were forged from iron, but over time, bronze barrels began to be cast, and there is evidence of short bronze barrels for some hand cannons too. These barrels, of course, did not yet have rifling, which negatively impacted shooting accuracy.

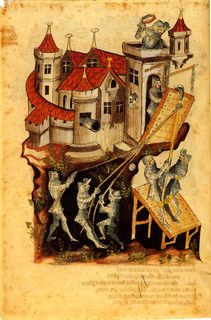

Lowering a drawbridge during a siege. The defenders are equipped with a cannon. Bellifortis, Konrad Kyeser, circa 1402. Wikimedia Commons

With the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the modern era after the year 1500, mechanical artillery completely disappeared, and the technology of casting bronze cannons continued to improve. Siege warfare techniques also improved, but that is another story...

Related products

And what to read next?

The Tale of Sir Radzig’s Sword

In the heart of Bohemian workshops, a replica has been forged of the sword known to millions of players around the world. In Kingdom Come: Deliverance, Sir Radzig Kobyla’s sword carries the weight of destiny. It was meant to be a gift from a father, but fell into the hands of the enemy. In the end, however, it was reclaimed and returned to its rightful owner. It became a symbol of loyalty and of the strength to endure in the face of adversity.

The Hussite Shock to Europe: How a Small Nation Changed the Continent

The Hussites were not merely heretics, as their enemies called them. They were the first to prove that it was possible to defend one's faith even against the whole of Christian Europe.

Trosky Castle

Trosky, the magical symbol of the Bohemian Paradise, hides a labyrinth of underground tunnels.

Jan Žižka of Trocnov, an ode to a brilliant military leader

He ranks among the most significant medieval commanders in European and Czech history—Jan Žižka of Trocnov (c. 1360 – October 11, 1424) is considered one of the undefeated giants of world battlefields. He gained fame for his use of the wagon fort, a highly effective defensive technique. His Hussite soldiers were pioneers in the use of firearms, particularly the "píšťala," a term from which the English word "pistol" is derived.