Gladiators

Death or Liberty or the Life of a Roman Gladiator

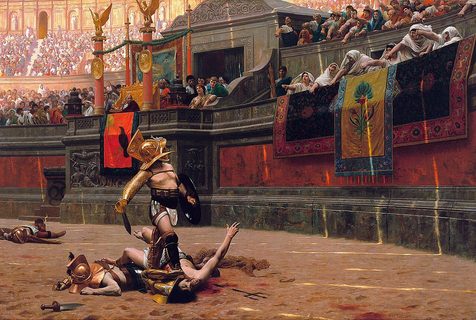

Facing both friends and foes, gladiators fought for their lives and the favor of the audience. Grueling training, fame or scorn, death or wealth—how did Roman gladiators live, fight, and die?

Gladiatorial contests in Roman arenas are rightly associated with man-to-man combat, mass slaughter, wild beasts, dust, and blood, all for the entertainment of a roaring crowd. Indeed, the reality of ancient Rome was brutal, and the repeated bloodshed in the arenas only emphasized this harshness. Yet, gladiators were still human, with their own desires, weaknesses, motivations, customs, and daily lives. This was true during the imperial period of Rome, just as it was during the early Republican era in the late 4th century BC when gladiatorial games first emerged as part of funeral rites honoring a deceased member of a prominent Roman family. These funeral games were private affairs, without state involvement, meant to ease the deceased’s passage to the afterlife while also showcasing the power and wealth of the family.

The School of Killing

Over several centuries, gladiatorial games took a completely different course. They were no longer funeral rituals but fully professional and organized events designed to entertain people on significant days and celebrate victories. In Italy, several specialized gladiatorial schools were established, and later others were founded in the provinces. The oldest written mention is of the school in Capua, which became the most important training ground for gladiators during the late Republic. The school of Lentulus Batiatus became famous due to Spartacus's uprising, and Julius Caesar also owned a gladiator school there. However, the largest and most significant school of the imperial era was Rome’s Ludus Magnus, built in the 1st century under Emperor Domitian as one of the imperial schools that replaced private schools in Rome.

There were several ways to become a student at such a gladiatorial school. The social status of gladiators was very low, roughly equivalent to that of prostitutes, partly due to the fact that most gladiators were recruited from slaves and prisoners of war who, by refusing to submit to the Roman concept of peace, lost control over their lives. If they weren’t executed outright, they ended up in bloody battles in the arena or were sentenced to gladiatorial schools, where they were trained to become professional fighters. It was the prisoners of war who initially made up the majority of gladiators because the cost of training warriors was not so high.

If a gladiator was a slave, it was often as punishment for a serious crime, such as murder, arson, desecration of a temple, or poisoning. Being sentenced to a gladiatorial school was practically a death sentence, with only a slim hope of mercy from the audience, which one might fight for. Roman citizens could also be condemned directly to the arena for crimes like murder, rape, or robbery. These so-called noxii lost all their rights and became mere "butcher’s meat," sent into the arena without training or armor to be slaughtered by professional gladiators—veterans. The last category of gladiatorial recruits were volunteers from among the citizens, motivated either by desperate financial situations or an unbridled admiration for champions and a desire for excitement.

Caring for Valuable Goods

Regardless of how they arrived at the school, all new gladiators were equal. One of the first things they had to do was swear an oath, in which the gladiator pledged to endure "being burned, bound, beaten, and killed by the sword." Every novice was immediately examined by a doctor, who was interested not only in their physical condition but also in their appearance and charisma, as not everyone was suitable for the gladiatorial show. Then experienced trainers—doctores, retired gladiators themselves—took over, teaching the recruits efficient combat techniques with specific weapons assigned to them by the school’s owner. Training was initially conducted with wooden weapons, with which the novices attacked a wooden post—palus—to build stamina and gain the necessary skills. The aim was to automate their movements. Sharp weapons were introduced later, and after each training session, they were returned to the guarded armory.

A gladiator was a significant investment for the school owner, requiring proper care. Therefore, alongside experienced trainers, gladiators had access to masseurs and doctors. They maintained their charges in good condition, ensuring that they didn’t suffer any serious injuries during training that would prevent them from putting on a quality performance in the arena. The high level of care for gladiators is evidenced by the fact that the famous Galen, later the personal physician to Emperor Marcus Aurelius, was one of these doctors. Galen worked for several years at the gladiatorial school in Pergamum, where only two gladiators succumbed to their injuries under his care, while his predecessor had a mortality rate thirty times higher. The quality of care, of course, varied depending on whether it was a small school in the provinces or an imperial school in Rome, where gladiators received top-notch service.

Barley Eaters

A nutritious diet was also crucial for the development and success of a gladiator. The foundation of the gladiatorial diet was barley, which was cooked into a porridge mixed with beans. The large consumption of barley earned gladiators the nickname hordearii, meaning "barley eaters." In general, the gladiatorial diet, called sagina, was not particularly popular among the gladiators, who ate in large communal dining halls. However, there was plenty of it, with a gladiator’s ration being larger than that of a legionary in the army—hearty and energetic, which the gladiators needed. On the other hand, Galen disapproved of such a diet, as it led to gladiators becoming overweight. He acknowledged, however, that a thick layer of fat protected gladiators from minor injuries. So, one should not imagine the average gladiator as a slim athlete with well-defined abs; skeletal remains have shown that they were more likely robust and slightly obese men.

When gladiators weren’t sweating during training or spilling blood in the arena, they spent their time in their rather austere accommodations, located along the training arena. Novices, of course, received the worst “cells,” while experienced professionals and the best among them could have more suitable accommodations. Typically, two or three men lived in a single small room. The furnishings of individual cells were very basic, with even beds missing, so gladiators likely slept on straw mattresses. The level of freedom gladiators enjoyed depended on their “origin.” If a gladiator was a prisoner of war or a criminal, he was considered untrustworthy and dangerous, so he was locked in his cell and guarded. On the other hand, if he was a volunteer or a Roman citizen, he could move freely.

Equality in Love

Even though gladiators were at the very bottom of the social ladder, this did not prevent them from being admired by women of all ages and social classes. For young girls, they were something of a platonic ideal, celebrated with inscriptions on walls, such as in Pompeii, where there is evidence that “Cresces, who catches girls in his net at night with his trident,” and “Celadus, the Thracian, who quickens the pulse of girls’ hearts.” For Roman women, including those of high rank, gladiators were objects of sexual desire.

It was not uncommon for noblewomen to choose their lovers from among the gladiators. Gladiators, whom we can without hesitation call the stars of the ancient entertainment industry, certainly had no shortage of female admirers. Likewise, gladiators were not denied sex, something that was a normal part of the world at the time and which their owners recognized as beneficial. Therefore, even those considered dangerous and kept under lock and key were allowed to receive visits from prostitutes, and some gladiators were even permitted to live with a woman.

Emperor or Gladiator?

Admiration for gladiators also extended to the highest levels of society. The most famous example of this is the obsession that gripped Emperor Commodus in the 2nd century. He was the successor of his father, Marcus Aurelius, but there were rumors that he was the illegitimate son of a gladiator. Commodus regularly performed in the arena under the name Hercules the Hunter. Everything was arranged so that the emperor wouldn’t be harmed. He shot wild animals from the gallery and allegedly killed a hundred bears at once.

Commodus chose his opponents himself, mostly inexperienced novices or people from the audience. Moreover, his opponents were often armed only with wooden swords. One story is enough to illustrate the emperor’s character. He gathered all those in the audience who didn’t have a left foot and had them fitted with “serpent tails” instead, armed them with sponges, and then, in the role of Hercules, beat them to death with a wooden club. If any gladiator excelled, the jealous emperor had him eliminated.